Indian Music Resources 1

Introduction to Swaras

(Swara = Note)

This introduction focuses on the natural resonances of the Harmonic Series, which underpin the concept of pitch in Indian Classical music.

In Indian Classical music, everything springs from the tonic, which is sounded throughout a performance. It is for this reason that Indian music has no harmony in the Western sense, nor does it modulate.

At least one tanpura (see figure 1) is present in a traditional performance. This is a drone instrument resembling a sitar, but without frets.

The tanpura generally has four open strings tuned to both the tonic and (almost exclusively) the 5th. These open strings are strummed repeatedly throughout a performance regardless of the rhythmic characteristics of the solo lines.

The characteristic strumming pattern of the tanpura is shown in figure 2:

The tanpura is extremely resonant, with very clear harmonics. In Indian music the harmonic series represents the ascent from the earth-bound to the transcendent. This is why Indian music is tuned in accordance with the harmonic series i.e. with “just” intonation.

Tuning framework:

Indian musicians tune the swaras to both the open strings and harmonics of the tanpura. In the past Indian music was always tuned in just intonation in relation to this drone. The rise of equal temperament in the west has unfortunately clouded this pristine purity of pitch, but luckily the finest Indian Classical musicians are keeping the tradition alive. My hope is that in bringing together these musicians with their Western colleagues in a way which enables this purity of pitch to be maintained, we are helping to nurture and propagate this ancient tradition of mathematically pure tuning.

The next section is a little technical, and aimed at string players, but it also illustrates the problem for any interested musician.

One of the difficulties Indian musicians find working with their Western colleagues is tuning in the upper register, especially when working with strings when the violin E string comes into play. The complaint is so often “I find it so hard to play with western players as they get so sharp when they go higher”.

This is because equal temperament results in mathematical ratios which are at odds with the simple proportions of the harmonic series. The open violin E string is gratingly sharp to the harmonic series of a tanpura tuned to C and G

Here is a direct solution to this problem that I have found very useful: tune the violin E strings to the harmonic series of the tanpura (and viola and cello C strings) specifically the 5th and 10th harmonics. It takes a little getting used to for the violinists as the violin E string will be “flat” to the A string, but this immediately prevents the spiraling up in pitch, and the instrument has a noticeably freer resonance

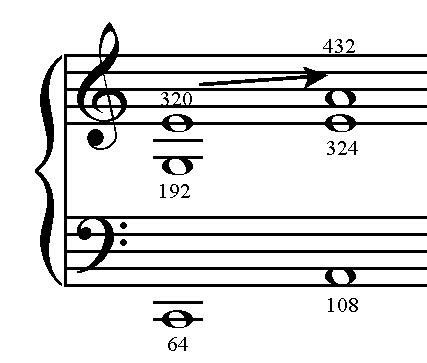

For people interested in the maths of this, figure 3 shows how the numberswork:

In figure 3, the upper number is the note’s position in the harmonic series

the lower number is the number of vibrations per second, and;

the arrows show where the notes of the harmonic series on the different

strings coincide

In order to keep the maths simple and avoiding recurring decimals, I have assumed a C below the bass stave of 64 Hertz

An interesting digression at this point: a cello C string tuned to C = 64 Hertz results in an A above middle C of 432 Hz. This is the pitch Verdi recommended in 1884. Symbolically this choice of pitch is significant. If C is viewed as the “primary” pitch, using this tuning all of the Cs are related to the number 1 through the series 1Hz,2Hz,4Hz,8,16,32,64,128,256,512Hz etc. Thus pitch is entwined with rhythm: the tonic is related to the average resting heartbeat, our fundamental measurement of time, something we will return to later in this series

Tuning Procedure for String Ensemble:

This simply follows the order of available open string pitches as they appear in the harmonic series of the fundamental tone (the low C of celli and bassi).

- Tune C strings to tanpura

- Tune G in accordance with the G present in the harmonic series of the C string (i.e. a pure, non-tempered 5th)

- Tune E strings in accordance with the E present in the harmonic series of the C string (i.e. a pure, non-tempered compound major3rd)

A beautifully pure C major chord should emerge at this point as we will be sounding the 1st, 3rd and 5th overtones of the fundamental C - After E strings have been tuned, tune D string to the D harmonic present in the harmonic series of the G string another pure 5th

- Tune A strings to the A present in harmonic series of D (and G!) strings another pure 5th

As mentioned above, the open E string will feel very noticeably “flat” to the A string (as it is tuned to the harmonic series of the C rather than A string). However, there will be a very satisfying resonance between E and C strings. This is because the violin E strings will be vibrating at exactly 10 times the rate of the Cello C strings.

Figure 3 also explains why the following phenomena occur:

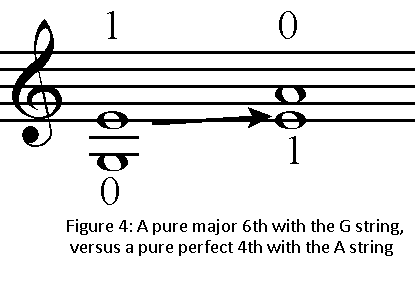

If a string player plays the example in figure 4, the first finger has to be noticeably sharper for a pure 4th with the A string than for a pure 6th with the G string

As figure 5 demonstrates, this is because each pair of notes is interpreted by the ear as belonging to a different harmonic series:

[twocol_one] [/twocol_one] [twocol_one_last]

[/twocol_one] [twocol_one_last]

[/twocol_one_last]

The major 6th (G and E in these examples) is interpreted by the ear as the 3rd and 5th overtones respectively of the harmonic series of C (see harmonic series chart above).

Because of the open A string, the perfect 4th (E to A) is interpreted by the ear as part of a harmonic series based on an A at the bottom of the bass stave.

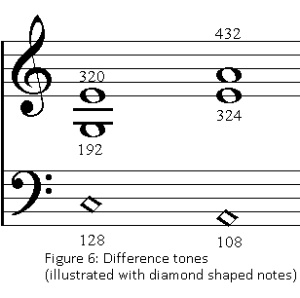

This happens because of the phenomena of the difference tone, (illustrated in figure 6 with diamond shaped notes) which is particularly noticeable when playing these examples with just intonation.

This happens because of the phenomena of the difference tone, (illustrated in figure 6 with diamond shaped notes) which is particularly noticeable when playing these examples with just intonation.

The difference tone is perceived because the difference between the number of vibrations of the first finger E (vibrating at 320 Hz) and the open G (vibrating at 192 Hz) is 320-192 = 128 Hz. A pitch of 128 Hz emerges.

This is audible as a note (known as the difference, combination or “Tartini” tone after the great violinist Giuseppe Tartini (1692-1770) who claimed to have discovered them. (See figure 7)

Tartini published his discoveries in a treatise “Trattato di musica secondo la vera scienza dell’armonia'” (Padua, 1754)

Returning to the example in figure 4, in listening to the second double stop, (the perfect 4th), the ear wants to hear the E and A in their most natural relationship. This is as the 3rd and 4th overtones of a fundamental A. Nature creates this low A out of the perfect 4th (432-324=108) and the resulting “Tartini tone” is also clearly audible.

Connecting Swaras tuned in just intonation – Slides and Ornaments

The expressive core of Indian music is between the notes. Slides, ornaments and expressive intonation all explore this space, and it is in this context that one encounters microtones. One school of Indian music theory divides the octave into 22 microtones, another into over 50; however in actual performance one experiences these microtones as the journey from one purely tuned note to the next.

In order to highlight the space between swaras, Indian string players use almost exclusively the 1st and 2nd fingers of the left hand (even for very rapid passages). In order to avoid being a caricature of Indian music the resulting slides need to be light and subtle. Think Kreisler and Casals!

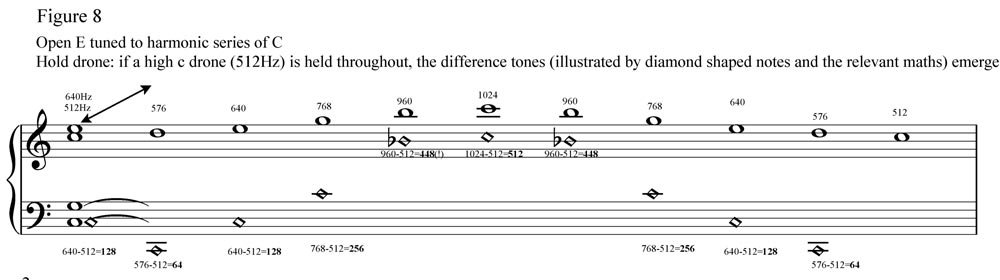

Practical Example: Raga of the Flying Swan (see figure 8)

These notes are the basis of the North Indian Raga “Flying Swan”. They can be used very effectively to get the feel for playing with natural intonation over a drone. If you play with a colleague holding the C above middle C, and the difference tones (illustrated with diamond shaped notes) emerge, you will know that you have achieved the optimum placing for each note.

If playing on your own, you can sit at the piano with your instrument, and keep a low C and G drone going with the sustaining pedal. Although a compromise, this also yields very interesting results. With your instrument (or voice) you can then improvise using the Flying Swan notes at slow, medium and fast tempi. You will find they naturally generate beautiful melodies almost by themselves, especially if you feel that you are exploring/unfolding the harmonic series, and that each combination of note and drone you play represents a different harmonic/emotional state.

Next stage: Slowly explore the space between these notes with gentle slides. This produces exquisitely dissonant harmonic states, which ultimately resolve when the note arrives at its rightful position in the harmonic series. This journey from what in the west would be called “out of tune” to “in tune” is a vital expressive device in Indian music. If you really keep your ears open to the difference tones whilst sliding, it is an incredible sound- they will be dancing wildly in the background!

Final Stage: Improvise melodies again in slow, medium and fast tempi. Make slides i.e. the space between the notes, an integral part of your expression.

Further reading: a really entertaining introduction to tuning issues is How Equal Temperament Ruined Harmony (and why you should care) by Ross W. Duffin and a marvelously comprehensive account is given by W. A. Mathieu in his brilliant work Harmonic Experience.

© 2013 David Murphy

Indian Music Resources 2

This section develops the concept of swaras in Indian music and introduces the elements of Indian music notation.

Indian music is played almost exclusively over a drone, and the pitch of this drone is chosen in order to enable voices or instruments to sound with optimum resonance. The most common pitch centres are C, C sharp or D.

Just like Tonic sol-fa system in Western music, Indian music has a system, known as Sargam where each swara is assigned a name. The default position of the swaras in relation to each other is formed by the notes of the Ionian mode, known in Indian music as Bilawaal Thaat, conveniently for the Western musician these are the notes of the major scale

If our tonic is D then:

[fourcol_one]

NOTE

D

E

F Sharp

G

A

B

C Sharp

D

[/fourcol_one] [fourcol_one]

DEGREE OF SCALE

Tonic

Supertonic

Mediant

Subdominant

Dominant

submediant

Leading Tone

Tonic

[/fourcol_one] [fourcol_one]

TONIC SOL FA NAME

Do

Re

Mi

Fa

So

La

Ti

Do

[/fourcol_one] [fourcol_one_last]

SARGAM NAME

SA

RE

GA

MA

PA

DHA

NI

SA

[/fourcol_one_last]

Some historical/philosophical background:

In ancient Indian music theory, each swara is said to relate to the sound of an animal, and also to correspond to a different part of the body

[threecol_one]

SWARA

SA

RE

GA

MA

PA

DHA

NI

[/threecol_one] [threecol_one]

ANIMAL

Peacock

Skylark

Goat

Dove

Nightingale

Horse

Elephant

[/threecol_one] [threecol_one_last]

LOCATION IN BODY

Base of spine

Sex organs

Solar plexus

Heart

Throat

Between eyebrows

Crown of head

[/threecol_one_last]

As in Western music, it is possible to chromatically alter many of the swaras to produce different ragas. In their default form (i.e. in the Ionian mode/major scale) each swara is known as shuddha. This is the swara’s “natural” position.

The tonic (SA) and the 5th (PA) are immovable. Only one swara is allowed to be sharpened by a semitone: this is the 4th (MA). When it is sharpened it is known as tivra so a sharp 4th is Tivra Ma.

Re, Ga, Dha and Ni can all be flattened by a semitone. When a note is flattened in this way it becomes komal so a flattened 7th for example is known as Komal Ni.

A line under a swara’s name means it is komal, so Komal Ni is written Ni or N.

A dash above or next to Ma (eg. M’) meants it is Tivra (sharpened).

Finally, a dot above a swara means it is in the upper octave (assuming a 3 octave range) and correspondingly, a dot below means it is in the lowest octave of this range.

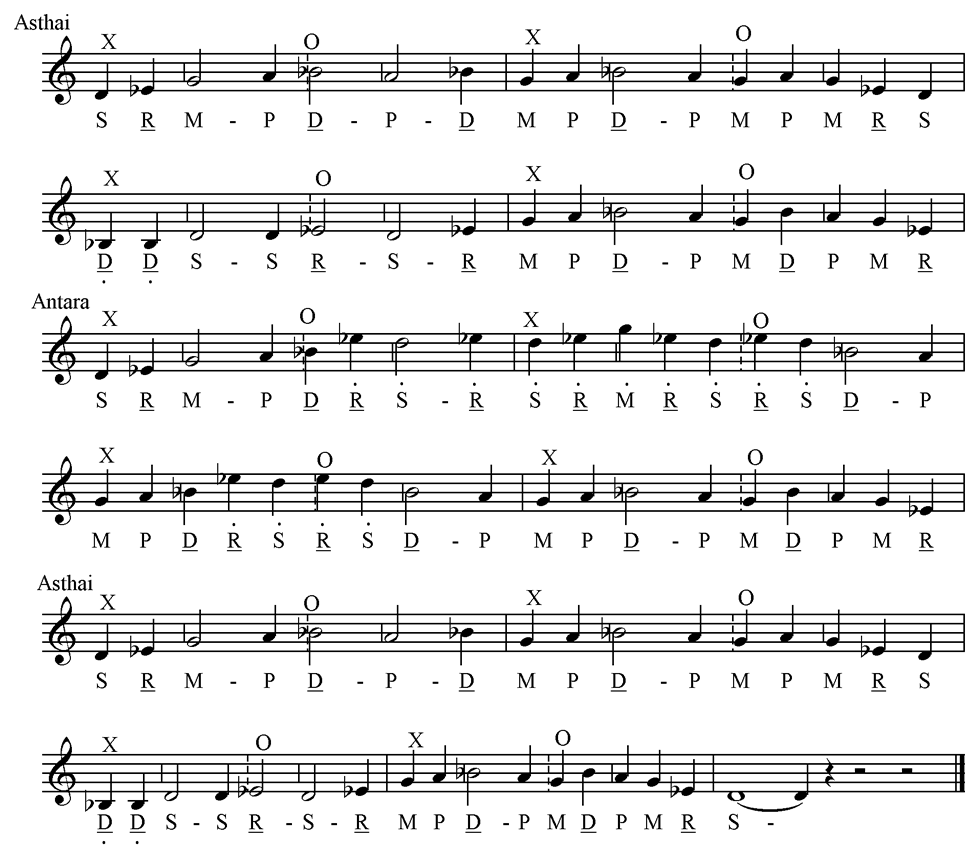

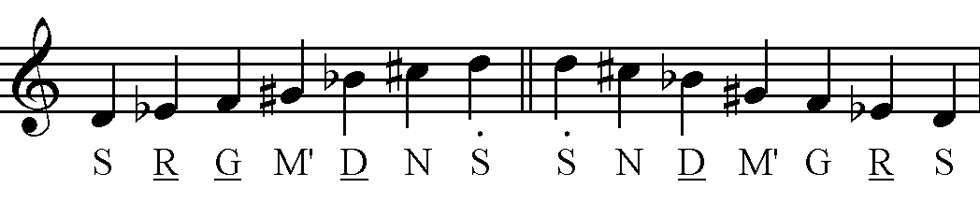

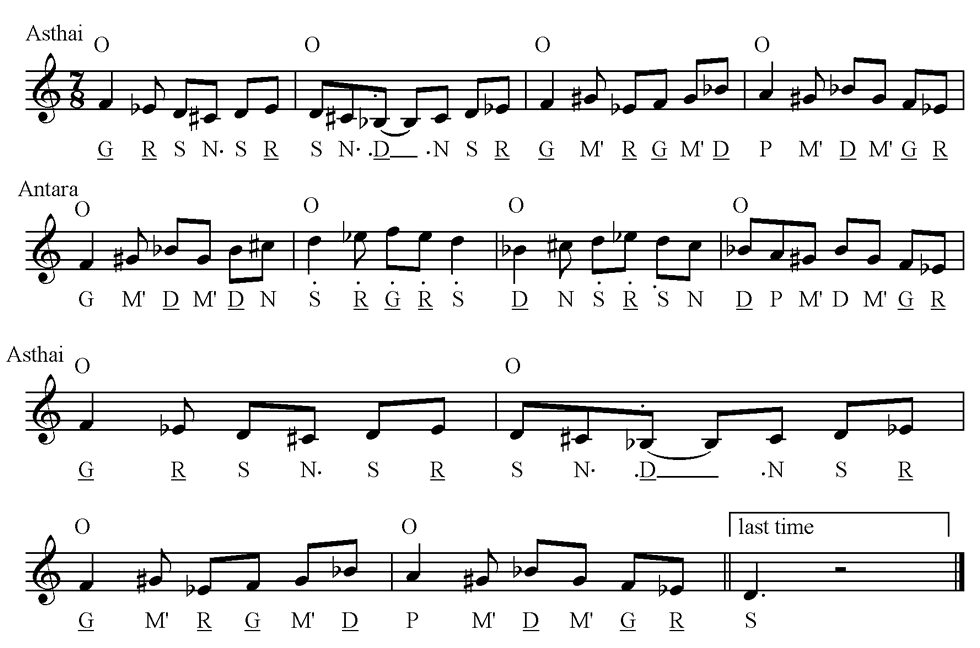

Figure 1 shows the swaras for one of the most fundamental ragas: Bhairav

Sargams are the first introduction the student of Indian music receives in raga forms, and Figure 2 is a Sargam in Rag Bhairav this particular sargam was much used by Pandit Ravi Shankar in his teaching.

The terms Asthai and Antara are introduced here for the first time. Both Asthai (“A” section) and Antara (“B” section) are normally repeated, giving an overall AABBAA form to the sargam.

Rather like a Western student learning an etude, one should memorise the sargam at a very slow tempo initially, gradually increasing the pace as the notes and spirit of the raga are absorbed. The commas indicate phrasing and the double bar lines in the example indicate the start of each 16 beat rhythmic cycle. (Rhythmic cycles are explored in section 3)

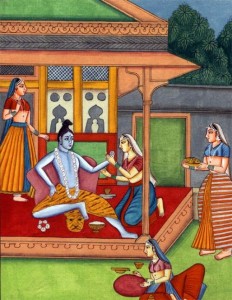

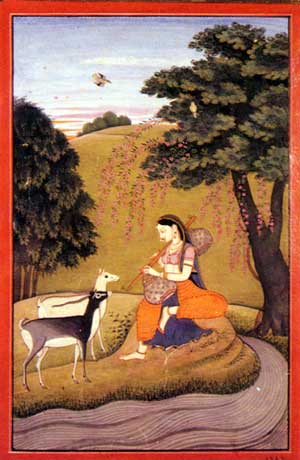

In Sanskrit there is a saying “Ranjayathi iti Ragah” which can be translated as “that which colours the mind is a raga. Each raga reflects a different emotional state, and over the centuries, visual artists have sought to capture these different states in “Ragamala” paintings. Figure 3 is a Ragamala depiction (c.1620) of Bhairav summing up visually some of the characteristics of the raga – “awesome grandeur, peace and devotion with a shade of melancholy.”

© 2013 David Murphy

Indian Music Resources 3

This section introduces 3 Rhythmic Cycles and two new Ragas.

Returning to the sargam in Rag Bhairav in the previous section, the beginning of each 16 beat rhythmic cycle is marked with a double bar line, thus this sargam begins half way through a 16 beat cycle.

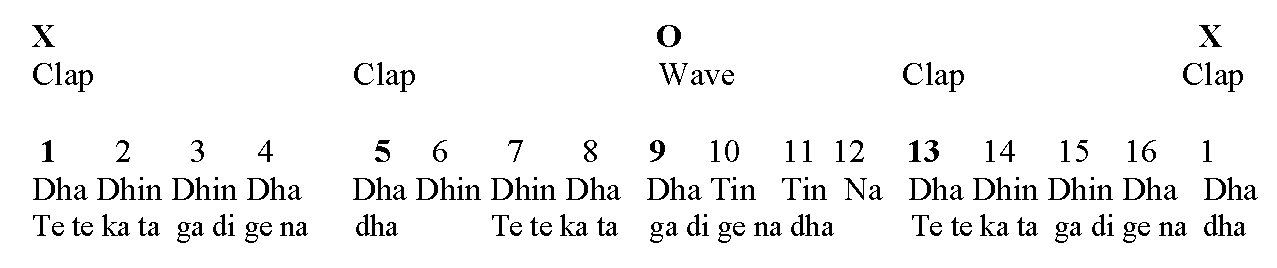

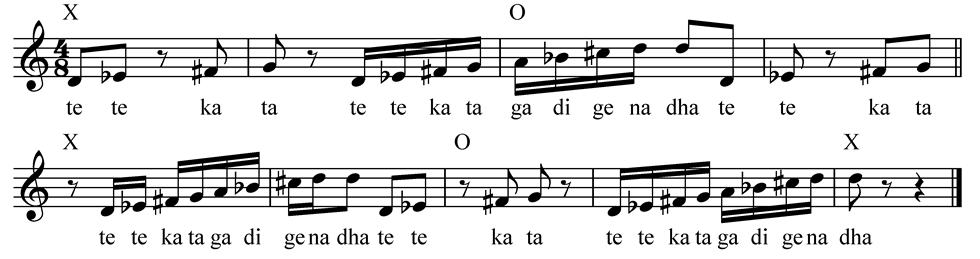

In Indian music, the rhythmic cycles are delineated by drum beats, or spoken with syllables that correspond to these drum beats (see drum line for a 16 beat cycle in the example below)

[fourcol_one]X

Clap

1 2 3 4

Dha Dhin Dhin Dha[/fourcol_one]

[fourcol_one][divider_flat]

Clap

5 6 7 8

Dha Dhin Dhin Dha[/fourcol_one]

[fourcol_one]O

Wave

9 10 11 12

Dha Tin Tin Na[/fourcol_one]

[fourcol_one_last][divider_flat]

Clap

13 14 15 16

Dha Dhin Dhin Dha (drums)[/fourcol_one_last]

This 16 beat cycle is known as Teental (or Tintal). It is divided into 4 vibhags (divisions or bars) of 4 beats. The first beat of the cycle is known as the Sam and is marked with an X. The 9th beat of the cycle is known as Kali (literally empty) and is marked with an O. Each vibhag can be marked with a clap, unless it is Kali, in which case it is marked by a wave.

A really useful exercise at this point would be to sing the Sargam in Rag Bhairav from section 2, vocalising the name of each swara, and clapping on the 1st and 5th beats of each rhythmic cycle, waving* on the 9th and clapping on the 13th.

*The waving motion is simply a palm up gesture, not a wave as in waving goodbye to a friend!

In order to develop a sense of the vast territory of Ragas and Talas, we will now meet two of each in quick succession.

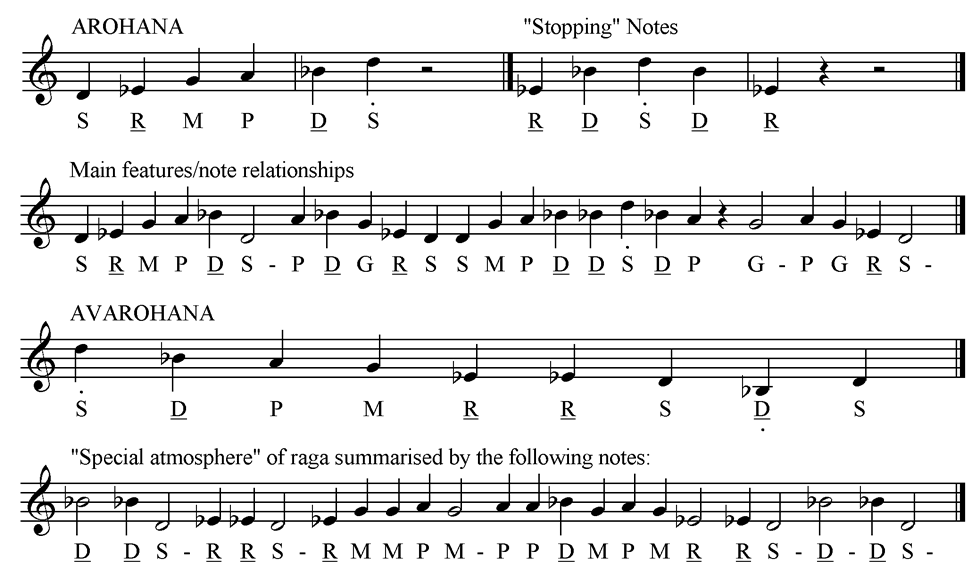

The first raga, GUNKALI is an early morning Raga traditionally used to create a focussed atmosphere. The notes of this raga are introduced in Figure 1.

Some new terms are also introduced here:

- Arohana = rising form of the raga

- Avarohana = descending form of the raga

The “stopping notes” in figure 1 are important notes in the raga on which one would often pause whilst improvising. The subsequent line of the example outlines the notes that are said to create the unique atmosphere of Gunkali

The rest of the figure 1 shows note patterns that further delineate the character of the raga. It is through note patterns such as these that one begins to understand what a raga is: an inspirational lattice of notes that could be defined as somewhere between a mode and a tone row.

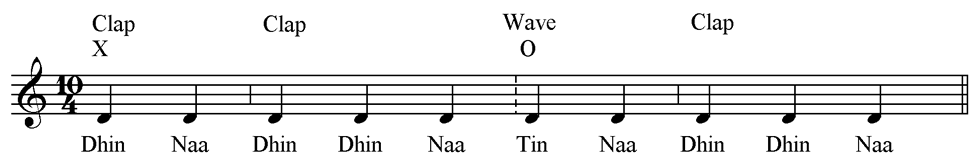

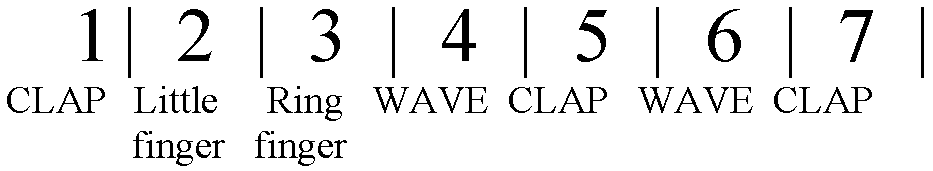

Figure 2 outlines a new rhythmic cycle or tala: Jhaptal. This is the most common 10 beat cycle in Indian music and is made up of 4 vibhags: arranged with the following matras (matra = beat).

In Figure 2, Dhin Naa Dhin Dhin Naa Tin Naa Dhin Dhin Naa is the Theka: the verbal representation of drum strokes.

Figure 3 presents a Sargam in Gunkali by Pandit Ravi Shankar.

This can be played on an instrument, and then sung with the corresponding hand gestures outlining the 10 beat rhythmic cycle.

Now we will meet Rag Todi and Rupak Tal.

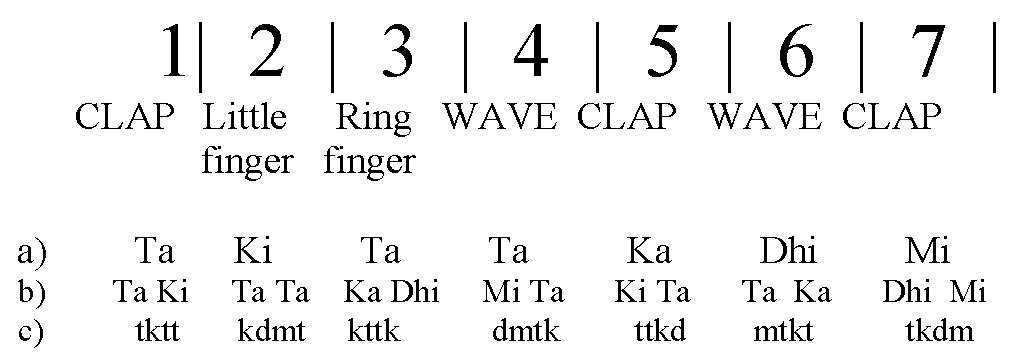

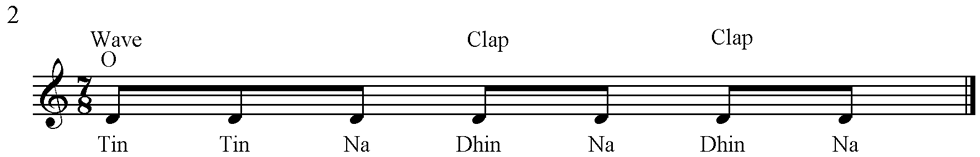

Figure 4 illustrates Rupak Tal: the most common 7 beat Tala in Hindustani music. It is unique because the Sam (1st beat of cycle) is Kali (empty)

Figure 5 outlines the notes of Rag Todi:

Drone: Sa (tonic) and Komal Dha (flattened 6th)

Figure 6 presents a Sargam in Rag Todi (also a morning raga) by Pandit Ravi Shankar, and Figure 7 is a Ragamala depiction of this important raga.

[fourcol_three]

[/fourcol_three] [fourcol_one_last]

[/fourcol_one_last]

© 2013 David Murphy

Indian Music Resources 4

Laya

Laya is an ancient concept rooted in the Vedic idea of an all embracing universal rhythm. A musician with an exceptional sense of rhythm is described as “having good laya“. In an inspired performance, the musician feels the pulse of the music, and the pulses of his or her body within this universal rhythm. In a traditional Indian music education, the student covers a progressive series of exercises designed to lead eventually to this goal.

Reminder: syllables corresponding to percussion strokes are used to organise rhythm. In North Indian Classical music, these are known as bols.

Here are the bols for the teental, the most common 16 beat cycle:

[fourcol_one]X

Dha Dhin Dhin Dha[/fourcol_one]

[fourcol_one][divider_flat]

Dha Dhin Dhin Dha[/fourcol_one]

[fourcol_one]O

Dha Tin Tin Na[/fourcol_one]

[fourcol_one_last][divider_flat]

Dha Dhin Dhin Dha[/fourcol_one_last]

A collection of bols forming a rhythmic “groove” as in the above teental example is known as the theka. (Theka can be translated as “support”).

Bols are also used for note groupings:

Ta

Ta Ka

Ta Ki Te

Ta Ka Dhi Mi

Ta Ka Ta Ki Te

Ta Ki Te Ta Ki Te (or Ta Ka Ta Ka Dhi Mi)

Ta Ki Te Ta Ka Dhi Mi

Ta Ka Dhi Mi Ta Ka Dhi Mi

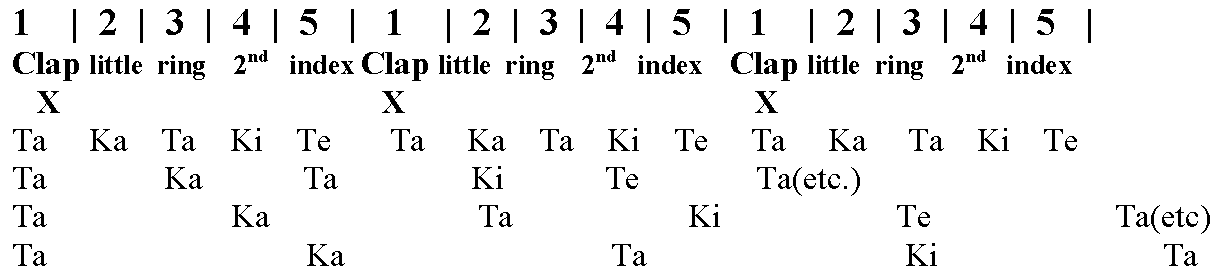

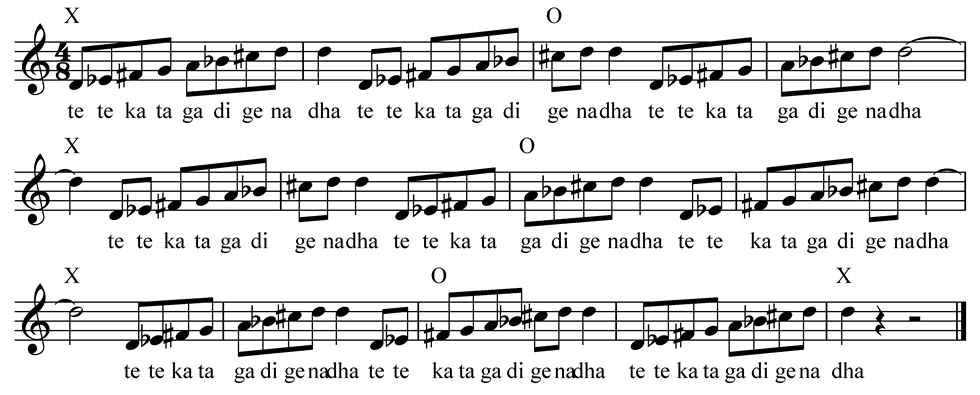

This system offers an incredibly practical and simple method of organising rhythm, see Figure 1.

Exercises such as the following are used by students of Indian music to develop the sense of rhythm.

These exercises explore rhythmic augmentation and diminution, and use Carnatic (South Indian) hand gestures plus bols:

Augmentation of a 5 beat pattern:

Bols for 5 beat grouping:

TaKaTaKiTe

The first line of bols below shows this pattern with one beat per syllable.

The subsequent lines spread the syllables out (one every two beats, then one every three etc.) whilst the clapping pattern remains the same.

Diminution of 7 beat pattern

Tala: Tisra Triputa (South Indian 7 beat cycle)

Firstly, practice the hand gesture for this pattern as outlined below. It begins identically to the 5 beat pattern above, but then the 4th and 6th beats are “waves” (palm up gestures) and the 5th and 7th beats simple claps:

The next stage is to get used to saying Ta Ki Ta Ta Ka Dhi Mi firstly with

1 syllable per beat (line a. below) then;

2 syllables per beat (line b. below) and finally;

4 syllables per beat (abbreviated as tktt etc in line c. below)

Stage 2: Laya exercises for singing & playing:

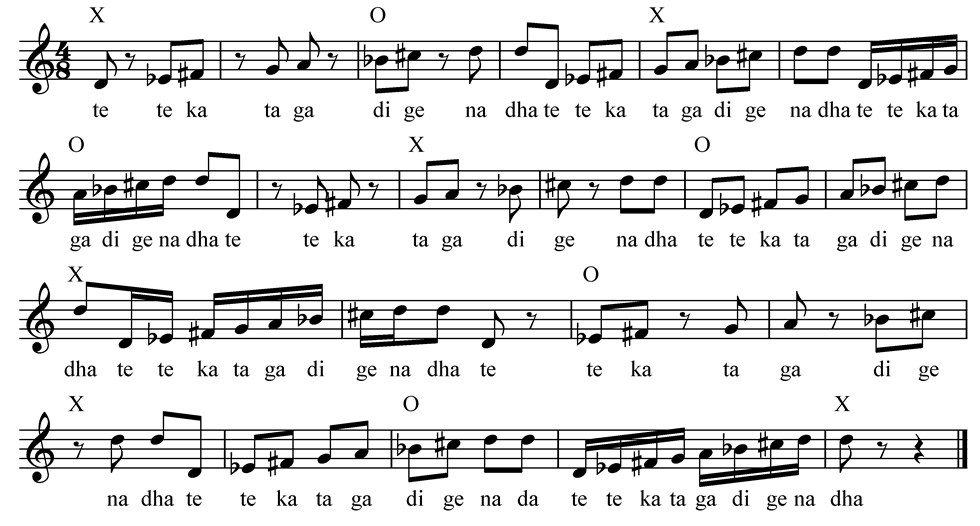

Now we will explore some rhythmic exercises which also involve pitch. They can be played on an instrument, but ideally will be sung to the sargam note names (Sa, Re, Ga etc.) clapping on each barline, except for those marked by a O (representing Kali or “empty”). On these barlines make the “wave” (palm up) gesture.

They are all shuddha in the Indian notation i.e. without any indications of komal (flat) or tivra (sharp). This is so that they can easily be sung or played in any of the 7 note ragas explored so far.

They are in Teental: each 16 beat cycle in the examples below being represented in the Western notation by 4 bars of 4/8

[fourcol_one]X

Clap

1 2 3 4

Dha Dhin Dhin Dha[/fourcol_one]

[fourcol_one][divider_flat]

Clap

5 6 7 8

Dha Dhin Dhin Dha[/fourcol_one]

[fourcol_one]O

Wave

9 10 11 12

Dha Tin Tin Na[/fourcol_one]

[fourcol_one_last][divider_flat]

Clap

13 14 15 16

Dha Dhin Dhin Dha (drums)[/fourcol_one_last]

Having mastered the syllables alone in the following examples, you can then move on to singing or playing them, using the Western notation as a guide.

Tihais:

A Tihai is a rhythmic pattern repeated three times. It serves a structural purpose in an improvisation, acting as a punctuation mark between sections.

The following examples are all in Teental. The ideal way to become familiar with the concept of the tihai is to establish the clapping/waving pattern for teental:

[fourcol_one]X

Clap

1 2 3 4

Dha Dhin Dhin Dha[/fourcol_one]

[fourcol_one][divider_flat]

Clap

5 6 7 8

Dha Dhin Dhin Dha[/fourcol_one]

[fourcol_one]O

Wave

9 10 11 12

Dha Tin Tin Na[/fourcol_one]

[fourcol_one_last][divider_flat]

Clap

13 14 15 16

Dha Dhin Dhin Dha (drums)[/fourcol_one_last]

If you are trying this exercise with a partner, get them to perform speak & clap/wave the drum syllables above (“Dha Dhin” etc.). Alternatively you could record them yourself.

The cycle of Teental provides the rhythmic underpinning for the Tihai. You can then say the syllables of the Tihai above the 16 beat cycle:

Having mastered the syllables alone in the examples (figures 5-8) you can then move on to singing and playing them, using the Western notation as a guide.

© 2013 David Murphy